By Michael Keith Olson, author of Tales from a Tin Can: The USS Dale from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay.

Herman Gaddis: We caught sight of the task force returning in the pre-dawn light and were very frightened. We had no radar and were under orders to maintain radio silence, so we had no way to signal our position to task force. The chief quartermaster “suggested strongly” to Ensign Radell that we break radio silence and call out our position before the task force blasted us out of the water. Much to the relief of everyone on the bridge, Radell picked up the mike and called us in. We soon formed up on the task force. Boy, was that ever a good feeling after a night of being dead in the water!

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

DECEMBER 7: JAPANESE ATTACK

Pilots aboard Nagumo’s six carriers awoke very early from what surely must have been a nervous sleep. Yet, despite all of the anxiety, Flight Commander Fuchida found Lieutenant Commander Shigeharu Murata, leader of the torpedo bombers who would soon strike Pearl Harbor’s battleship row, hungrily wolfing down a hearty breakfast. Murata called out, “Good morning, Commander Fuchida. Honolulu sleeps!”

“How do you know?” Fuchida asked.

“The Honolulu radio plays soft music,” Murata responded. “Everything is fine!”

At 0600, Nagumo’s six carriers began launching the first wave of airplanes. At 0630, Commander Fuchida turned south in command of forty Kate torpedo bombers, fifty-one dive-bombers, forty-three fighters, and forty-nine Kate high-level bombers. Months of training were about to culminate in an operation that would commit Japan to a war with the industrial might of the United States.

Though most of Honolulu slept, a few were being made aware that something was up. In the early morning darkness, the destroyer USS Ward (DD-139) spotted the periscope of an unidentified submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The Ward attacked the submarine, sank it, and then reported the incident up the chain of command. Then, at approximately 0700, an alert army radar operator saw the approaching first wave of Japanese airplanes on his scope and called in a report to his superior. Both reports, however, fell on deaf ears and nothing was done to increase Pearl Harbor’s readiness for what was about to come from the sky.

Harold Reichert: Some mornings, the waters of Pearl Harbor would be so still the seaplane pilots could not see where to land, and so we’d have to send out the motor whaleboat to stir up the water a bit. On mornings like that, you could always pick up the smells of fuel oil mixed with tropical flowers, and after a week or two at sea those smells were mighty inviting. My Sunday morning ritual at Pearl was to sit out on the fantail with a cup of coffee and a newspaper and enjoy the early sun and those tropical airs.

Cliff Huntley: In the peacetime navy, it was customary to give weekend liberty to two-thirds of Dale’s crew when we were in port. Three of us had gone together and purchased a much-used 1935 Chevrolet. The two-thirds rule meant that on any given weekend, two of us owners would have the car. On that weekend, Ensign Vellis and I drove the car into town to spend the night in some nice rooms across the street from the Moana Hotel. It was always great to get off the ship and get into Honolulu, a beautiful place with many small homes and maybe one-third the population of today.

Harold Reichert: There were ninety-six ships in Pearl Harbor that morning and no reason to expect any trouble. After all, the Honolulu Advertiser I was reading told how Japanese Ambassador Nomura was going to meet with the Secretary Cordell Hull in Washington that very morning to talk about peace.

0700 to 0755

As the first wave of attacking Japanese airplanes approached the north shore of Oahu, two reconnaissance planes launched earlier reported the U.S. fleet to be asleep at Pearl Harbor. While there was no sign of an alert, there were also no aircraft carriers tied up at the moorings on the north side of Ford Island. This piece of news greatly frustrated Commander Fuchida, as the carriers were his primary objective. But the battleships were lined up like bowling pins along battleship row. Fuchida radioed in code to Nomura, and all of Japan, “To . . . To . . . To . . . [attack, attack, attack] Ra . . . Ra . . . Ra . . . [success, success, success].” At the time, American radio operators translated the two separate syllables as the single word tora, Japanese for “tiger.”

Fuchida’s fighters were the first to arrive in the air over Oahu. They fanned out over the island, established air superiority, and then commenced strafing the American airplanes parked wing to wing on the ramps of various air bases around the island. Next came his dive-bombers, which dove on ships and facilities. Then came the lumbering Kate torpedo bombers, which headed straight for battleship row. Finally, above it all, flew the level bombers with 16-inch armor-piercing naval rounds specially adapted for dropping from on high.

Dellmar Smith: I was sitting on a forward torpedo tube with a cup of coffee, talking with Humphrey. We saw a big bunch of airplanes coming in over the mountains and got to wondering which carrier they belonged to.

They could not be coming from the Saratoga, because she was in dry dock in Bremerton; nor the Enterprise, because she was participating in an exercise way down south somewhere. And the Lexington had just gone to sea Saturday, so it was doubtful her planes were flying back already. It just didn’t make any sense. So we watched as they flew in from the mountains. Then, when they got to about a hundred yards away, Humphrey jumped up and said, “Goddamn! They’re Japanese!”

Don Schneider: I had the messenger duty that night, which meant I didn’t get to sleep until four in the morning. I was working as a mess cook, so my bunk space was down in the mess hall, where there were always a lot of guys coming and going. Mess cooks were at the bottom of the ship’s totem pole, and sleeping mess cooks were fair game for whoever happened to come through. When someone came by yelling that the Japs were attacking, I yelled back, “Go to hell!” and rolled over for more sleep.

Warren Deppe: We were eating breakfast down in the mess hall. At the time, we had aboard this chief torpedoman we called “Sailor Boy White,” who was the ship’s practical joker. One of his favorite gags in those days, when everyone’s nerves were on edge, was to sneak into a compartment when nobody was looking and yell, “The Japs are coming! The Japs are coming!” And so, when Sailor Boy White came running into the galley with a terribly frightened look on his face that morning, nobody paid him any attention, even when he started pleading that he was telling the truth. Then we heard the explosions!

Harold Reichert: Just then, a plane flew by at about thirty feet. I could see the pilot plain as day. He wore a leather helmet with straps under his chin and a pair of goggles. I could see the whites of his eyes, and he was totally fixed on the old Utah, which was an old battlewagon the navy had stripped down and converted to a target ship. She had a big wooden deck on her, so dive-bombers could practice bombing her with sandbags. She looked a lot like an aircraft carrier and was even anchored in the same berth the Lexington had vacated the previous day!

I did not realize what the plane was until I finally got focused on the big red rising sun painted on the fuselage. And then I saw the torpedo drop and watched as it ran up on the old Utah. The explosion sent a huge fountain of water shooting way up high into the air. I remember dropping my newspaper and yelling, “We’re being attacked!”

Johnny Miller: I had the radio duty and was sitting at my desk reading the Sunday morning funny papers when I heard some unexplained explosions. Just then one of the fellows came by the radio room yelling, “The Japs are attacking!” I ran outside just as a torpedo plane came across our bow and let go his torpedo at the battleship Utah. I even noticed the smile on the pilot’s face he was so close. Heck! I could have hit him with a rock!

Ernest Schnabel: I was absorbed in my Sunday morning crossword puzzle when I heard some aircraft flying real close. I looked up and saw two planes flying by at about masthead height. Then I heard explosions on the light cruiser Raleigh and the old Utah.

J. E. McIntyre: I had just finished breakfast when the GQ alarm went off. To get to my station in number one fire room, I had to go topside. When I did, a Japanese torpedo bomber flew by so close I could have hit it with a potato—if I had one. I then went below to the fire room and didn’t come up again until the next day.

Jim Sturgill: I was sleeping in when the general quarters alarm clanged away and sailors began throwing gas masks, helmets, and elbows everywhere. I jumped out of bed, got dressed, and ran topside. When I stuck my head out the hatch, I saw explosions throughout the harbor and burning ships. My stomach fell and I knew in an instant that we were at war.

Alvis Harris: I was down below, brushing my teeth and getting ready to visit a neighbor from back home who was stationed aboard the battleship West Virginia. There was a huge commotion, so I ran outside to see what was going on. The first thing I saw was a Japanese bomber dropping its torpedo, which then ran right up into the old Utah and exploded.

Mike Callahan: I was to have the duty at twelve noon and so went to early mass. While the service was going on, we heard a tremendous amount of gunfire, and I wondered why they were having exercises so early on a Sunday morning. Then someone burst into the church and yelled, “We’re being attacked!” I ran outside and knew in a second it was true.

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: I ran up to the OOD, who was a young ensign, and said, “Sir, the Goddamn Japs are attacking!”

He said, “Ah, you’re full of baloney!”

Then I said, “Well, go back and take a look at the Utah, if you don’t believe me.” He went back and looked at the Utah, which had just been hit with a torpedo.

Harold Reichert: My general quarters station was at gun two, which was up forward. So, when that torpedo hit the old Utah, I took off as fast as I could. As I was moving along the length of the ship, I passed the ward room, where a frightened-looking ensign was standing in the hatchway. “We’re being attacked, sir,” I said without slowing down.

John Cruce: A young ensign was standing in the hatchway with his jaws wide open. I ran past him yelling, “We’re at war, sir!” I kept right on a-running until I reached the galley, where I pulled the general quarters alarm.

Cliff Huntley: We heard the bombing in our rooms across the street from the Moana Hotel, clear up in Honolulu. We dressed as fast as possible, jumped into the Chevrolet, and raced off toward Pearl Harbor, where we abandoned the car at the gate. It was the last any of us ever saw of that old Chevrolet!

|

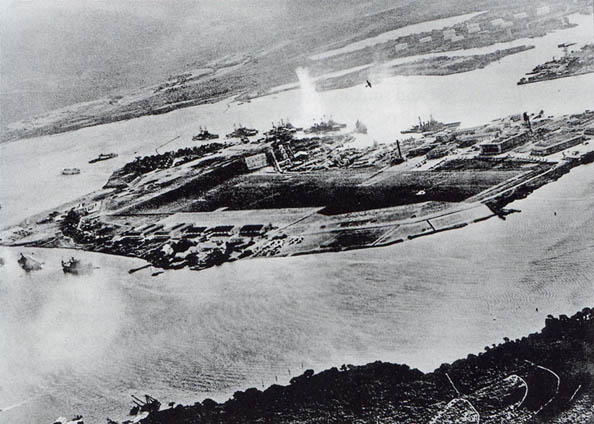

| Pearl Harbor -- 0600, December 7, 1941. |

0755 to 0820

With no aircraft carriers to attack, the Japanese pilots focused their attention on battleships, seven of which were tied up along battleship row on the north side of Ford Island. The remaining one, the USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), lay in dry dock across the channel.

Within the first two minutes of the attack, all of the battleships along battleship row had taken hits from dive-bombers. The torpedo attacks took longer, as many pilots took two or three runs before actually launching their torpedoes. The anchored U.S. fleet was at a low state of readiness, and a few of the ships’ machine guns were manned. The Nevada (BB-36), for example, had machine guns manned in her fighting tops, and consequently suffered only one torpedo hit, as compared to the six that hit West Virginia (BB-48), four on the Oklahoma (BB-37), two on the California (BB-44), and one on the Arizona (BB-39).

As the attacking planes sent torpedo after torpedo slamming into the battleships, Oklahoma rolled over onto her side and sank into the bay. West Virginia also took on a severe list, but counterflooding by daring seamen prevented her from rolling over and allowed her to settle onto the bottom on an even keel. The California, Maryland (BB-46), and Tennessee (BB-43) also suffered varying degrees of damage in the first half hour of the raid.

Despite the explosions that filled the harbor area with fire and smoke, the Japanese pilots, well trained from months of practice, maintained discipline. Most of their attack runs were made in coordinated groups of three to five planes. Many of the strafing fighters came in very low, sometimes passing within a few feet of the ground in pursuit of targets, which often included cars or people.

At about 0810, the Arizona was hit by one of the modified 16-inch armor-piercing naval rounds dropped by a level bomber. The round penetrated the Arizona’s deck near turret two and ignited in the ship’s forward ammunition magazine, mortally wounding the ship. The resulting explosion and fire killed 1,177 crewmen. Those serving on ships near the exploding Arizona that day would say, “It rained sailors!”

Harold Reichert: I got to my general quarters station at gun two before anyone else and even before the GQ klaxon sounded. By then, there were explosions everywhere, and I looked around for what to do next.

Each of our 5-inch guns needed a powderman, shellman, pointer, gun captain, and phone talker. Trouble was, most of our crew was ashore, including the older married guys, who were the ones who knew how to do everything. And that was not the least of it either, because we were tied up at Berth X-14 with three other cans. The order was Aylwin, Farragut, Dale, and Monaghan, which meant we were sandwiched tight between two other cans, and none of our forward guns could bear without shooting up our sister ships!

Johnny Miller: I dashed down to the radio shack and started the ball rolling. We came up on every important frequency I could think of. The Harbor frequency was the one on which all the important messages were coming over. The first message I copied was, “Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is no drill!” Next was a message for all ships to get under way. Then the frequency became almost useless due to the Japs causing interference and sending out messages for all to cease fire.

John Cruce: We had no gunnery officer, no firing pins, no powder, no first-class petty officer to install the firing pins—if we could ever find them—and no orders to fire!

Herman Gaddis: The Officer of the Deck up on the bridge, Ensign Radell, hadn’t been in the navy more than a year and was shaking like a leaf because he was now the acting captain of a U.S. Navy ship at war. But we also had a thirty-year chief petty officer up there, and he said, “Relax, son. We’ll make it out of here just fine!” So they worked things out together and soon put out orders to set material condition Affirm and light off all the boilers!

J. E. McIntyre: When I got to my GQ station in number one fire room, the only person there was Lead Fireman Schnabel. I asked, “What are we supposed to do now?”

“Get the hell out of here as fast as possible!” Schnabel answered.

“Get out of this fire room, or get out of Pearl Harbor?” I replied.

“Let’s light her off and get her out of Pearl Harbor!” he said. Luckily, we had the ready duty Saturday, and our boilers were still warm. Otherwise, we were cold iron.

But then I said, “We can’t fire the boilers because they’re full of water!”

“You take care of the fire, and I’ll take care of the water,” he ordered, and then opened the drain valves and started to drain the warm water straight into the bilges. Usually we lowered the water levels gradually by pumping the water overboard, but that morning, time was not allowing.

Harold Reichert: I looked up and saw a guy climbing way up to the top of the stacks. I watched him for a moment and realized he was trying to cut loose the stack covers. Whenever the burners weren’t lit, the stacks would be covered to keep the rain out. But when the stacks were covered, there was no way to light off the burners because they couldn’t get enough air. The bosun mates that had covered the stacks were all ashore when the Japanese attacked. So someone had to climb up there and cut the stack covers free, and all he had was a small pocket knife!

Herman Gaddis: Up on the bridge, things became pretty intense when we found ourselves looking straight down the muzzle of one of the Farragut’s 5-inch guns. Now the Farragut was tied up directly to our port side, and they were shooting wildly about at anything that moved. Ensign Radell ran out on the flying bridge yelling, “Point that damn thing the other way!”

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: I was the pointer on the forward 5-inch gun. But there was no place to point because the Farragut was tied up to port, the Monaghan was tied up to starboard, and the Japanese torpedo bombers were flying real low.

Herman Gaddis: We had this black mess attendant aboard named Dixon who was very popular with the crew. He came running up to the bridge and said, “Our five-inch guns can’t fire because they don’t have firing pins!” We then realized all the firing pins were in the gunner’s mate’s locker, and the gunner’s mate was ashore somewhere. While the rest of us froze with the impossibility of the situation, Dixon ran down to the locker, broke in, grabbed up all the firing pins, and handed them out to the gun crews.

John Cruce: I asked for permission from the bridge to open fire, but no one answered. Since there was nobody up there to say “No,” we went right ahead and blasted away at the next Jap plane to fly by. Our ammo was really bad, and our shots kept going off way behind the targets. I kept yelling down to the fuse cutter, “Cut the fuses! Cut the fuses!”

A. L. Rorschach, Captain’s Log: The presence of ships on either side of Dale prevented the use of all forward guns. The forward twenty-four-inch searchlight made it impossible to bring the [gun] director to bear in the direction of the level bombing attacks on the battleships. The 5-inch guns operated in local control with very poor results, the shots bursting well behind and short of the targets, a squadron of level bombers flying at about ten thousand feet above the battleships on alternately northerly and southerly courses. 0815 an enemy dive-bomber attacking the USS Raleigh from westward came under severe machine-gun fire from all the ships in the nest, nosed down, and crashed into the harbor.

Jim Sturgill: Back aft on gun five, we had enough clearance from the other ships in the nest to aim and shoot, but our ammunition was locked up tight and no one could find a key. So I took a hammer and broke open the locker. The gun captain said, “You’re going to be court-marshaled for this!” I just shrugged him off and started shooting just as a big torpedo bomber came lumbering by. We blasted him and he went down in flames.

Author’s note: Two army P-40 fighters managed to take off and shoot down five Japanese planes. One of the pilots, Lieutenant George Welch, was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but was denied the honor because he had taken off without orders.

Alvis Harris: In the radio shack we were up on the Air Raid, Harbor, and Channel frequencies. Orders and information came in fast and furious like, “All ships get under way immediately” and “DesDiv Two, establish offshore patrol. Enemy submarines sighted inside and outside Pearl Harbor!” I was running messages back and forth to the bridge and got to see a lot of the action. I saw the Utah, Raleigh, and Detroit being bombed, torpedoed, and machine-gunned. I saw the Raleigh settle down on the bottom, and the Utah turn upside down. The sky was a mass of exploding AA with Japanese bombers flying in and out of them.

Johnny Miller: The next time I dashed up to the bridge I saw a horrible sight. The USS Utah had turned over and was lying with only her bottom showing. I could see the big bomber hanger over on Ford Island alive with flames. The USS Arizona was afire and sinking fast. The West Virginia was hit with six or seven torpedoes and was afire. The USS Nevada was hit by a torpedo and was heading for the beach so she wouldn’t sink.

J. E. McIntyre: While tied up in the nest with the other tin cans, we got all of our steam and power from the Monaghan’s boilers. So when she cast off, we were “cold iron.” Under normal conditions, it took us about a hundred and fifty minutes to fire up our boilers. But there was nothing normal about that Sunday morning! After Schnabel flushed the water, I lit off all four boilers and began pumping the crude oil. Since our boilers were still warm, we were able to get up enough steam to get under way in nineteen minutes!

Don Schneider: When I got up to gun one, things were moving real fast. Someone handed me a fire axe and told me to chop the line to the Monaghan, which was tied up to starboard. When I finished chopping, they sent me to the ammunition handling room. Someone was down below in the magazine, and they were sending up powder and 5-inch rounds as fast as they could. Trouble was, we weren’t shooting at anything yet, so the ammunition was piling up and crowding us out of the handling room, and whoever was down there wouldn’t stop. I started stacking some of the rounds out on the deck, but someone running by bumped into my stack and sent a couple of the 5-inch rounds rolling across the deck and over the side.

Harold Reichert: The Monaghan had the ready duty that Sunday morning and so was ready to go first. I was happy to help throw off her lines, because it meant that gun two would finally have a clear field of fire to the east.

Johnny Miller: The Monaghan backed away from the nest and headed for the channel entrance. A Jap submarine periscope was sticking up out of the water, and the USS Curtis was firing into the water with her guns, trying her best to sink the sub. The

Monaghan let out a blast on her horn to signal she was making a depth charge attack. She had to have a lot of speed on to clear the area of the explosion or be damaged from her own depth charges, and this caused her to run aground.

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: Immediately after the Monaghan cast off, it made a high-speed run on a midget Japanese submarine it had spotted and dropped two 600-pound depth charges. The explosions lifted the rear end of the Monaghan clean out of the water. If I close my eyes, I can still see her screws spinning wildly in the air!

A few moments later, we cast off, and as we were backing out, I happened to look up through the open turret of the gun and saw two white torpedo streaks coming straight at us just under the surface of the water. Luckily for us, Dale was due to tie up at the tender on Monday, and so we were low on everything and only drawing about nine feet of water. Those torpedoes streaked right underneath us and blew up on Ford Island.

Don Schneider: We figured out later how the miniature Jap submarines managed to sneak past the submarine nets into Pearl Harbor. That Saturday we escorted the Lexington out to sea, picked up the old Utah, and then followed her back into the harbor. There was quite a bit of room between the Utah and the Dale going in. Those little subs must have just jumped in line between the two of us and followed the sound of the Utah’s screws as she worked her way up into the harbor.

Johnny Miller: One torpedo came whizzing by our bow, but missed us by a few feet. Another came from the stern and went under us, hit the beach, exploded, and tore the beach up for yards around.

Harold Reichert: It usually took hours to get under way, but on that Sunday morning, it only took minutes. The interesting thing about being in battle is that you don’t get to see much of it, even when you are in the middle of it!

0820 to 0855

By 0830, the first wave of attacking Japanese airplanes had spent themselves and were winging their way north to the carriers. A lull settled in over Pearl Harbor as sailors and soldiers prepared for further attacks.

During this lull in the action, the Nevada, the one battleship capable of getting up steam, got under way and began moving slowly down the channel toward the harbor entrance and open sea. The sight of this towering battleship moving along amid the flames and smoke brought hope to those trapped in the flaming hell of Pearl Harbor. But before the Nevada could move very far, she was jumped by the second wave of Fuchida’s attackers. Pilots of this wave, which consisted of 170 airplanes, found Nevada to be the opportunity for which they had been looking. If they could sink Nevada in the channel, they could bottle up Pearl Harbor for months to come. In a few frenzied moments, the Japanese pilots dropped five armor-piercing bombs onto the lumbering giant. The Nevada, under the command of a junior officer, then received orders from the harbor control tower to stay clear of the channel. This left the young officer with one course of action, and that was to beach the Nevada and thereby prevent her from sinking.

While the Nevada was attempting her sortie, more dive-bombers and fighters appeared in the skies over Pearl Harbor.

Unlike pilots of the first wave, whose attack had been carefully choreographed by Nagumo’s planners, pilots of the second wave were given free rein to attack targets of opportunity.

Groups of airplanes circled high in the sky looking down through the smoke for good targets, which were quickly found tied up in Pearl Harbor’s dockyards and dry docks. The battleship Pennsylvania (BB-38), sitting high in a dry dock, was hit by an armor-piercing bomb dropped from a level bomber, while destroyers Cassin (DD-372), Downes (DD-375), and Shaw (DD-373) were completely destroyed by bombs and fire. Still, the most important target of all for the attackers would be the one they could catch trying to sneak out of the harbor.

Alvis Harris: When we got under way, the first ship we passed was the Monaghan, which was stuck in the mud after making a high-speed depth charge run on a Japanese submarine. She was just moving too fast to avoid running aground, so she got stuck in the mud. Eight Jap planes were attacking her, and she was shooting back at them like mad. We could see her screws backing furiously trying to get her off that mud.

Johnny Miller: As we passed the Monaghan, guys on both ships waved a friendly goodbye.

Alvis Harris: Then we passed by the old Utah, which was rolling over and going under. She had just tied up at the Lexington’s berth the day before! All this time I was just a-standing there in the hatchway of the radio shack, a-gawkin’ at all this like some old country boy.

Ernest Schnabel: As we left our berth and got under way, the deck force was still engaged in getting ready for combat. One young bosun named Fuller had the job of clearing the deck of all the wooden objects that collected in port. And there was a lot of it, because in port we had all these awnings rigged to keep the tropical sun off the decks. You also had to get rid of all the wooden swabs, buckets, and boxes, because if a machine-gun bullet from a Japanese plane were to strike any of it, slivers would fly all over the place just like shrapnel.

So Fuller was making his way aft, just tossing stuff like a madman when he came to the wooden ice cream gedunk. He grabbed it and was just starting to push it over the side when one of the guys said, “Hey, wait a minute!”

Back in 1941, ice cream was a mighty precious commodity in the destroyer navy. Today you can find ice cream and sugar candy on almost any street corner, but back then, we tin can sailors had to get our ice cream off the bigger ships that had the equipment to make it. They almost always figured out ways to make us pay for it, too! So that young bosun struck a nerve when he made moves to toss all the ship’s ice cream over the side.

In a matter of seconds, the lock was broken and the ice cream distributed among the crew. Then Fuller kicked the empty wooden gedunk over the side. So, what you saw was the USS Dale steaming hell-bent out into the channel, while the guys back aft were standing by their guns eating ice cream and watching World War II break out all around them.

Harold Reichert: Then we passed by the Nevada, which was backing down the other channel. Her crew was pumping water over the side like crazy with portable pumps rigged up with handy-billys. You could tell she was going to try and beach herself on the mud to keep the channel clear.

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: The minute we got around the Nevada, all hell broke loose. Before that, we were like spectators at someone else’s fight. The Japs didn’t pay us much attention, attacking the bigger ships instead. But when we rounded the Nevada, they came after us with just about everything they had. We were the first ship to head out of Pearl Harbor, and they wanted to sink us in the channel and bottle up the fleet.

Johnny Miller: We were in a select position to be the first ship in the channel, and the high-level bombers were waiting for us. If they could sink us, they would block up the channel and then have a field day with all the ships trapped in the harbor. The bombs they were using were 16-inch armor-piercing battleship rounds with fins welded to them. Being only thirty-four feet wide, the bombs straddled us and sank deep into the mud before they exploded and showered us with mud and rocks.

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: There were bombs falling all around. And they were armor-piercing bombs, which buried themselves deep in the mud on the bottom of the channel before blowing up. The explosions sent huge fountains of water and stinking mud up higher than Dale’s radio mast. That’s when we really opened up with every gun we had.

Eugene Brewer: On the way out, I was stationed aft at the manual steering hatch cover in case we lost steering on the bridge. An enemy plane dropped two bombs at us. One hit to the starboard, and the other fell into the water right next to the boat davit where I was standing. The explosion sent up a huge fountain of stinking mud that fell all over us. But nobody panicked. It was like being in a movie where everyone was calm even though all hell is breaking loose.

Warren Deppe: Our depth charges and torpedoes were locked up in the magazines down below, and our job was to get them all up on deck and ready to use. We had to lift them up to the deck with chain falls, and then get their exploder mechanisms together. The exploders were little tubes about two inches long that contained fulminate of mercury, which was very explosive and could easily blow up in your hands. You had to load that tube of mercury into the torpedoes and depth charges while Dale was steaming full speed up the channel and the Jap planes were dropping bombs on us.

Harold Reichert: We saw a plane flying low and slow out in the sugar cane fields and started blasting away at it. Thinking back, I also remember seeing a few civilian cars on the road that were most likely out for a Sunday morning drive. Our ammo and our aim were so erratic I’ll bet we scared the hell out of those drivers! Probably the safest place to be that morning was in that Jap plane!

J. E. McIntyre: We usually steamed out of Pearl Harbor at a very careful five knots. But on Sunday, December 7, 1941, we steamed out at twenty-five knots!

John Cruce: The big question on the way out was the sub net. Was it open or closed? The net was a barricade stretched across the harbor entrance to prevent submarines from sneaking into the harbor. It had a little tender that stretched it back and forth. If the net was closed, we were in big trouble because we’d be penned in and a perfect sitting duck for the Jap planes trying so hard to sink us. So everyone aboard was hoping to see it open. And it was!

Author’s note: Japanese submarines played a big part in the attack on Pearl Harbor. In fact, their presence so unnerved the admirals commanding the fleet they allowed only their destroyers to leave, believing the harbor was still the safest place to shelter the capital ships from the hoards of U-boats they believed were lurking outside. Even as the Dale was making its escape, the harbor was being sealed up tight.

Johnny Miller: When we passed the submarine nets, we were making thirty knots. Shrapnel was falling like rain around us as a result of all the antiaircraft fire. As we passed the first entrance buoy to the channel, we sighted a formation of silver bombers flying high in the clouds. Next a bomb struck close to the starboard side and blew mud and salt water all over the ship. Another skipper bomb landed close to the port side, barely missing us. Another passed our stern and still another crossed our bow. They were trying their best to sink us and block the channel. The Dale must have been wearing her good luck charm, for nary a thing touched us.

A. L. Rorschach, Captain’s Log: At 0907, cleared the entrance buoys and by stopping the port engine and coming hard left rudder, caused a flight of three enemy dive-bombers to overshoot their mark. As they went by on the starboard side close to the water, machine-gun fire from Dale struck the leading plane causing it to burst into flame and crash into the water on the outer starboard side of the restricted area. The remaining two planes made a half-hearted attempt to attack again but were driven off by machine-gun fire.

John Cruce: We darned near took a bomb running out of the channel. We made a hard turn to port, and the bomb landed exactly where we would have been. The explosion threw mud clean up over the bridge and the entire ship. Though it missed us, the concussion did knock out a circuit breaker on our port lube pump. And nobody noticed it was out. This would cause us big trouble a little later.

Don Schneider: When we got out of the harbor, we got orders over the radio to look for the Jap fleet, as nobody knew where it was. We were all afraid the Jap battleships would steam in from over the horizon and finish off what the airplanes had missed. It would have been pretty easy for them to do, as Pearl Harbor was a complete shambles and unable to protect itself. They could have steamed back and forth ten miles off shore and just wiped us clean out with their big guns.

Dellmar Smith: My battle station was in the aft fire room, and so I didn’t get to see much of the action. In fact, I was so busy with getting up steam, I figured all the explosions I was hearing were just us depth-charging that two-man sub the Monaghan was after. Later, I got to thinking about all those explosions and wondered if we ever

got that sub, so I asked a bosun mate. “Depth charges, hell!” he said. “Those were bombs dropped by the dive-bombers that were trying to sink us and block the harbor!”

0910 to 1930

Fuchida’s second wave of attackers did not escape unscathed, as most of the twenty-nine Japanese airplanes lost that day were shot down during this attack. Nevertheless, the attackers did manage to inflict major damage to ships and facilities, and especially to the Army Air Corps airplanes, most of which had been parked wingtip to wingtip in order to protect them from being sabotaged. By 1030, Fuchida’s last attacker was flying back to Nagumo’s carriers.

On board the carrier Akagi, Admiral Nagumo and staff nervously awaited Commander Fuchida’s report on the attack at Pearl Harbor. They had an important decision to make as to whether to launch additional attacks. This decision was certain to be a hotly contested one.

When Fuchida’s force returned, his undamaged airplanes were re-armed for possible action against the missing American carriers. The American carriers did not appear. After a brief meeting with his pilots, Fuchida met with Nagumo and recommended additional attacks to destroy the remaining facilities at Pearl Harbor. But the cautious Nagumo had had enough. He quickly dismissed Fuchida and turned his carrier force back toward Japan. There would be no follow-up attack and no attempt to find the missing American carriers. Nagumo’s decision was a great stroke of luck to the Americans, as the tank farms and repair facilities of Pearl Harbor were left largely intact.

A. L. Rorschach, Captain’s Log: 0911, the Dale established offshore patrols in sector one. Due to repeated airplane attacks the ship was forced to make frequent changes of course and to run at high speed, thereby rendering the sound gear inoperative. It may be of interest to note that a great number of the bursts on the water were of the nature of exploding 5-inch shells rather than bombs. It is believed that either the fuses were not cut on many of our 5-inch projectiles, or that they were not operative.

Jim Sturgill: Outside, we passed some Japanese sampans running for Honolulu. They were flying white flags from their masts. And they were white flags, not rags or pieces of clothing! Without thinking, I grabbed a rifle and took aim. But before I could shoot, someone grabbed the rifle away.

A. L. Rorschach, Captain’s Log: 1114, the USS Worden (Commander Destroyer Squadron One) sortied. The Dale formed on the Worden as the third ship in column. After investigating the falsely reported presence of the three enemy transports off Barbers Point, formed inner anti-submarine screen on the USS Detroit, Phoenix, St. Louis, and Astoria. The Dale was assigned station nine. The Task Force speed was twenty-five knots. At 1410, the L.P. pinion bearings on the reduction gear of the port engine wiped. An attempt was made to stay with the assigned Task Force, but as the maximum speed attainable with one engine was twenty-two knots, the Dale fell steadily behind. The starboard engine began heating excessively, forcing a further reduction of speed to ten knots. Retired to the southward at 1654. Stopped at 1930 and lay to attempting repairs.

Harold Reichert: When we lay to, things got real quiet, real fast. There were no other ships. We did not know where the Japs were. We did not know where our task force was. There was just us, stopped dead in the night under complete radio silence.

1930 to 0500

Nagumo’s fleet was now on its way back to a triumphant reception in Japan. The American sailors and soldiers, however, were in the dark as to the location of the Japanese. Surely, the Yanks thought, the Japanese fleet is out there somewhere, getting ready for another attack. This time they will bring the big guns of their battleships! After all, we don’t have anything left that can stop them!

Jim Sturgill: There were two crews aboard Dale that night. One crew was made up of all of us trying to fix the burned out pinion bearing. The other crew was made up of those waiting for the bearing to get fixed. I’m glad I was one of the fixers, because the waiters really had it tough that night!

Alvis Harris: We were under radio silence all night long, but that didn’t keep us from monitoring the traffic. And there was a lot of it to monitor! All night long, we got plain language broadcasts out of Pearl. Some broadcasts said Pearl was being attacked again. Others said the Jap fleet was steaming in for another attack. It was all panic gossip, but since we were under orders not to use our radio, we just had to sit there and listen all night.

Eugene Brewer: We were the perfect target for the Japanese subs that seemed to be just about everywhere that day. Why heck, we had been dropping depth charges on them all day long, and now it was night, and we were dead in the water! But maybe even worse than the Japanese subs were our own ships, which were shooting first and asking questions later. Someone got the bright idea to drape our largest American flag over the torpedo tubes so our own forces wouldn’t shoot us up. But that sure didn’t solve our submarine problem!

John Cruce: Dale’s decks were crowded with crew that night, because nobody wanted to be caught down below if we were going to be torpedoed. The only sailors down below were those trying to fix the bearing. Everyone else stayed topside and watched for submarines.

Ernest “Dutch” Smith: I had been without sleep for thirty hours and was still too afraid to go below. Sometime, way deep in the early hours, I finally just curled up on the deck and fell asleep.

Harold Reichert: It hit me hard the night we were laying to outside Pearl Harbor. We were at war! And I just knew it was going to be a long, long war. Where would it take me? Would I survive? Would I ever get to see home again? And I knew the war was going to be just like that day, December 7th, had been. We simply would never know what was going to happen to us next!

Jim Sturgill: We pulled the pinion bearing out, saw that it was scoured pretty badly, and took it up to the machine shop. We had a lot of help up there. Too much help! Nobody liked being dead in the water with all those enemy subs out there, so everyone wanted to help fix the bearing!

We put the bearing, which was about seven feet long with an eight-inch journal, into the machine shop’s twelve-inch lathe. We got it to fit between the centers okay, but couldn’t get the tool arm back far enough to make it turn the bearing’s surface. So we filed down the rough edges of the scoured surface by hand. Then we took emery cloth and wooden blocks and polished it the best we could. It wasn’t the best job, but it was good enough to get us running again, to the relief of everyone on the ship!

Excerpted with permission from Tales from a Tin Can: The USS Dale from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay.

Copyright © 2007, 2010 by Michael Keith Olson.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

No comments:

Post a Comment